Friday 27 June 2014

CHUCK NOLL, BILL NUNN: Race And The Pittsburgh Steelers

My monthly off-season FMTE column is now up at nfluk.com, you can link to it here. (Update: that link seems to have expired as of September 2016; you can find the whole article reprinted in my appreciation of Bill Nunn III here). It looks at Chuck Noll, the now-legendary Pittsburgh Steelers coach, and Bill Nunn, the scout who covered the traditionally black colleges for the team, and should be legendary. Even if you're not interested in football, per se, this is a fascinating slice of life in a very different NFL.

Thursday 26 June 2014

STEPHANIE KWOLEK: THE GUARDIAN OBITUARY

My obituary of Stephanie Kwolek, who invented Kevlar, is up at the Guardian online (you can link to it here) and ought to be in the paper paper soon. It's a fascinating story, mostly because of the accidental nature of her invention; as it seems is so often the case, she was perceptive and curious enough to take an experiment others might have considered failed, and pursue it just another step further.

My obituary of Stephanie Kwolek, who invented Kevlar, is up at the Guardian online (you can link to it here) and ought to be in the paper paper soon. It's a fascinating story, mostly because of the accidental nature of her invention; as it seems is so often the case, she was perceptive and curious enough to take an experiment others might have considered failed, and pursue it just another step further.

I might have made more of Kwolek's success in an overwhelmingly male profession, an overwhelmingly male lab environment, at a time when the deck was stacked against women in the work place anyway. It intrigued me that she appears to have devoted herself to her work; there was no indication of survivors nor relationships, which isn't to say she had none.

I mentioned she was the first, and remains the only, woman to be awarded DuPont's Lavoisier research award; I had also written she was only the fourth woman inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, and that she was also inducted into the National Women's Hall Of Fame, but those mentioned were edited out. As was the mention of a children's book about her,The Woman Who Invented

the Thread That Stops Bullets.

THE AFGHAN WAR FILM: THE FILM PROGRAMME DISCUSSION

I was on BBC Radio 4's Film Programme today (we taped it yesterday). It's available on I player (link to it here), and will also be repeated on Sunday at 11pm; it's the first item on the show. Francine Stock and I had a fascinating conversation, both on and off air, which was cut down considerably for the slot; what remains is largely the wider view, which makes sense following the Peter Berg interview about Lone Survivor.

I was on BBC Radio 4's Film Programme today (we taped it yesterday). It's available on I player (link to it here), and will also be repeated on Sunday at 11pm; it's the first item on the show. Francine Stock and I had a fascinating conversation, both on and off air, which was cut down considerably for the slot; what remains is largely the wider view, which makes sense following the Peter Berg interview about Lone Survivor.Doing the research for the interview, I realised there are quite a few Afghan war films I not only had not seen, but which had barely made an impression on me. We didn't record a conversation of why these films have made less impact than a number about Iraq, but I may review some here at IT along the way.

We did discuss the two versions of Brothers, Susanne Bier's Danish one starring Ulrich Thomsen, and the American remake, directed by the Irishman Jim Sheridan, with Toby Maguire and Jake Gyllenhall. I pointed out that the Danish experience in the Middle East has had significant play in their TV series shown here, not only Borgen but some of the crime series as well, and more significantly that I am convinced Brothers is the source material, or inspiration, for Homeland.

We did discuss the two versions of Brothers, Susanne Bier's Danish one starring Ulrich Thomsen, and the American remake, directed by the Irishman Jim Sheridan, with Toby Maguire and Jake Gyllenhall. I pointed out that the Danish experience in the Middle East has had significant play in their TV series shown here, not only Borgen but some of the crime series as well, and more significantly that I am convinced Brothers is the source material, or inspiration, for Homeland.Homeland was also a connecting point for me, to examine how wars that are unpopular, or at least not being fought by the country as a whole (the Bush wars are now 11 years old, and still make little impact on the home front--people scream 'support the troops' and keep their children home to watch American Idol) produce films that tend to concentrate on the effect of the war on us. In our discussion I had declared Three Kings the best of the movies set in these specific wars, but it had the advantage of that war's being over, and the ambiguity of our withdrawal as its political core. Most of the early, successful, films about Vietnam were about the home front, not just The Deer Hunter (which I still consider hollow) but Coming Home, Tracks, Rolling Thunder, and Who'll Stop The Rain (aka Dog Soldiers). Taxi Driver is part of that bunch too. Of course there were allegorical critiques, like MASH, Catch 22, or Soldier Blue.

The best of the recent homefront movies is probably In The Valley Of Elah, where Tommy Lee Jones hardens director Paul Haggis' more liberal instincts. But you heard Francine mention Lions For Lambs, which we actually discussed in the tapings--I called it a remake of Starship Troopers which dares to question Ayn Rand.

We used to be less triumphalist. The British think their war films are more realistic and more understated, but they aren't. Look at the World War II combat films produced during the war, and how many of them involve loss and last stands. They Were Expendable, Air Force, Bataan, Corregidor, Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, are the films of a nation who like to feel themselves the underdogs.

We used to be less triumphalist. The British think their war films are more realistic and more understated, but they aren't. Look at the World War II combat films produced during the war, and how many of them involve loss and last stands. They Were Expendable, Air Force, Bataan, Corregidor, Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, are the films of a nation who like to feel themselves the underdogs.We also mentioned 9th Company, Fyodor Bondarchuk's movie set in the Soviet war in Afghanistan, which I'm going to see soon and write about, and we didn't get to talk enough about the specific documentaries.

And though when they called I assumed it was to ask me to talk about Jersey Boys, as I've written The Pocket Essential Clint Eastwood and I am old enough to have bought Four Seasons' 45s, I did at least get to talk to Francine about Clint's next film,

American Sniper, which, like Lone Survivor, is based on Navy Seals, in this case the memoir of a Seal sniper. It's interesting that Clint played an assassin in Where Eagles Dare, a very Sergio Leone character in Kelly's Heroes, but when it came to war movies he's made only three: the very triumphal, very cliched, and basically Green Berets update (with victory at the end) Heartbreak Ridge, and then the much more sombre Flags Of Our Fathers and Letters From Iwo Jima, both very much about the kinds of issues which Peter Berg described, the horrible toll taken on men at war. So I'm looking forward to seeing what sort of take Clint brings to that one.

American Sniper, which, like Lone Survivor, is based on Navy Seals, in this case the memoir of a Seal sniper. It's interesting that Clint played an assassin in Where Eagles Dare, a very Sergio Leone character in Kelly's Heroes, but when it came to war movies he's made only three: the very triumphal, very cliched, and basically Green Berets update (with victory at the end) Heartbreak Ridge, and then the much more sombre Flags Of Our Fathers and Letters From Iwo Jima, both very much about the kinds of issues which Peter Berg described, the horrible toll taken on men at war. So I'm looking forward to seeing what sort of take Clint brings to that one. Tuesday 24 June 2014

CORRECTION, I JUST CAN'T MAKE IT, CORRECTION: GERRY GOFFIN & BARRY GOLDBERG IN THE GUARDIAN

I'm afraid I just couldn't resist when, in Dave Laing's otherwise fine

obituary of Gerry Goffin, he spoke of Goffin pairing up with guitarist

Barry Goldberg to write 'more political' songs. My letter of correction

is online at the Guardian now, you can see it here or if you don't like links, here it is:

I'm afraid I just couldn't resist when, in Dave Laing's otherwise fine

obituary of Gerry Goffin, he spoke of Goffin pairing up with guitarist

Barry Goldberg to write 'more political' songs. My letter of correction

is online at the Guardian now, you can see it here or if you don't like links, here it is:"Barry Goldberg, with whom Gerry Goffin wrote songs in the 1970s, was a keyboard player, not a guitarist, from a Chicago blues background (and the band the Electric Flag). And far from being more political, the pair's biggest hit was I've Got to Use My Imagination, for Gladys Knight & the Pips."

The Barry Goldberg Reunion's There's No Hole In My Soul was one of my early favourite records. He then went on to play in some of my all-time best: the Electric Flag, on their great first album, in Al Kooper and Mike Bloomfield's Super Session (though you have to listen hard),

and made another great record, with Bloomfield playing under the alias 'Great' called Two Jews Blues. Bob Dylan produced the eponymous Barry Goldberg, which has been re-issued recently with the original vocals; Jerry Wexler made Goldberg re-record his vocals and they weren't as good. He also played in one of the least super of the super groups, KGB.

and made another great record, with Bloomfield playing under the alias 'Great' called Two Jews Blues. Bob Dylan produced the eponymous Barry Goldberg, which has been re-issued recently with the original vocals; Jerry Wexler made Goldberg re-record his vocals and they weren't as good. He also played in one of the least super of the super groups, KGB.That Chicago scene, made up of young white kids in love with Chicago blues, included Bloomfield, Paul Butterfield, Goldberg, Steve Miller (the Goldberg-Miller Blues Band was their early group), Harvey Mandel, Nick Graventies, and many others, and they made some great music. And 'I've Got To Use My Imagination' is a really fine song. You can listen to it here.

Wednesday 18 June 2014

JOE GAETJENS, WORLD CUP ICON:THE GLOBALIST REPORT

I've done a retelling of the story of Joe Gaetjens, the Haitian who scored the only goal for the US when they defeated England 1-0 in the 1950 World Cup in Brazil. You can hear it at Monocle.com, on their programme The Globalist (link to it here) about 36 minutes in.

I've done a retelling of the story of Joe Gaetjens, the Haitian who scored the only goal for the US when they defeated England 1-0 in the 1950 World Cup in Brazil. You can hear it at Monocle.com, on their programme The Globalist (link to it here) about 36 minutes in.I wrote about the game, and some of the misconceptions around it, four years ago, you can find that essay right here at IT. I did write an update of sorts, but thus far no one is interested. Maybe if the US advance. I should point out the US and England drew 1-1 in that 2010 match, so the English still haven't managed to beat us in a World Cup match. Ever.

Friday 13 June 2014

JAZZ LIVES: MILT HINTON AND LEE FRIEDLANDER AT YALE, THE JAZZ JOURNAL REVIEW

My review of this exceptional exhibition is now up at Jazz Journal, you can link to it here. Although it looks great, I've taken the liberty of posting it here, choosing some additional photos from the dozen Yale provided,and arranging others differently, which I think reflect the review better. I wish I had the space to use more...

My review of this exceptional exhibition is now up at Jazz Journal, you can link to it here. Although it looks great, I've taken the liberty of posting it here, choosing some additional photos from the dozen Yale provided,and arranging others differently, which I think reflect the review better. I wish I had the space to use more...

It's not often you get

to see side-by-side two very different artists approaching the same

material, but that's exactly what's on display in a moving exhibition

at the Yale University Art Gallery. The subject matter, broadly

speaking, is jazz music, and the photographers are Milt Hinton and

Lee Friedlander. To borrow a metaphor from American football of their

era, the two men are Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside.

In 1957, one of

Hinton's students, David Berger, came across a pile of negatives and

contact sheets in Hinton's apartment. It wasn't long before Hinton's

photographs were being taken very seriously, and not just those of

the jazz world. But within that world of jazz, his work provides the

kind of backstage perspective few could match. Matched with an

uncanny ability to capture the essence of people within the moment,

to tell their story with subtle directness, it makes these pictures

masterful.

The most famous

photograph in jazz history may be the one Art Kane took for Esquire

magazine, of New York's jazz men gathered on a Harlem stoop. It's

been the subject of its own documentary, A Great Day In Harlem

(1998), in which Hinton and his own photographs (as well as 8mm movie

footage taken by his wife Mona) featured greatly.  Hinton captured the

camaraderie of these musicians—in the unusual situation of all

being awake and about early in their days; and the joy of the day, as

well as the jostling for a good position in the final photo, is plain

to see. They tell you more about the people that you could ever

divine from the group shot.

Hinton captured the

camaraderie of these musicians—in the unusual situation of all

being awake and about early in their days; and the joy of the day, as

well as the jostling for a good position in the final photo, is plain

to see. They tell you more about the people that you could ever

divine from the group shot.

Hinton captured the

camaraderie of these musicians—in the unusual situation of all

being awake and about early in their days; and the joy of the day, as

well as the jostling for a good position in the final photo, is plain

to see. They tell you more about the people that you could ever

divine from the group shot.

Hinton captured the

camaraderie of these musicians—in the unusual situation of all

being awake and about early in their days; and the joy of the day, as

well as the jostling for a good position in the final photo, is plain

to see. They tell you more about the people that you could ever

divine from the group shot.

But there are much less

joyful images too, that tear at the heart. We see Holiday in the

studio, in 1957. Hinton's focused on her, and the soft background

turns Count Basie, Freddie Green, and Jo Jones into almost ethereal

presences behind her haloed intensity. Two years later, she's back in

the studio, and it's as if the life has been drained from her bones;

Hinton catches her with a drink, bent over before the microphone, all

that halo disappeared.

Sobering in a different

way are the shots of his band mates on tour. Beyond the telling

picture of Danny Barker and Gillespie sleeping in their seats on a

train, there are many shots of musicians posed in front of

whites-only hotels, lunch joints, restrooms—places they can't leave

their bus to enter. In another, Mona poses with Ike Quebec,  Doc

Cheetam and others, pointing to the 'Motel For Colored' sign behind

them. Those contrast with the relaxed feel of musicians lined up in

1955 at the bar at Beefsteak Charlie's in New York, men at work

relaxing in their environment. Hinton was an innovator with the 'slap

bass', and there's a raucous improvisational feel at work here.

Doc

Cheetam and others, pointing to the 'Motel For Colored' sign behind

them. Those contrast with the relaxed feel of musicians lined up in

1955 at the bar at Beefsteak Charlie's in New York, men at work

relaxing in their environment. Hinton was an innovator with the 'slap

bass', and there's a raucous improvisational feel at work here.

Doc

Cheetam and others, pointing to the 'Motel For Colored' sign behind

them. Those contrast with the relaxed feel of musicians lined up in

1955 at the bar at Beefsteak Charlie's in New York, men at work

relaxing in their environment. Hinton was an innovator with the 'slap

bass', and there's a raucous improvisational feel at work here.

Doc

Cheetam and others, pointing to the 'Motel For Colored' sign behind

them. Those contrast with the relaxed feel of musicians lined up in

1955 at the bar at Beefsteak Charlie's in New York, men at work

relaxing in their environment. Hinton was an innovator with the 'slap

bass', and there's a raucous improvisational feel at work here.

Beyond that there's a

magnificent shot of Cannonball Adderly, contemplating ten pages of

unfolded sheet music stretched out in front of him, as if to answer

those who felt jazz musicians were simply following 'natural

talents'. There's a dissipated Gene Krupa, looking as tragic as

Holiday, and a young Sam Cooke radiant behind the glass in a

recording booth. And there's a stunning portrait of Ike Quebec, with

pianist Freddie Roach behind him, blowing the blues in the Blue Note

studios in 1961. Hinton catches every instinct of jazz music, the way

it expressed such a multitude of feelings, often contradictory, of

genius refusing to be stifled, and humanity refusing to be denied. As

both musician and photographer, this was the core of Hinton.

There's a similar sense

of humanity in Friedlander's work, but it approaches the subject from

a different perspective. Born in 1934, Friedlander is Mr. Outside. He

studied in Los Angeles, but moved to New York where he worked as a

freelance photographer for outlets as varied as Esquire and Sports

Illustrated, as well as doing liner photos for Atlantic Records. As a

jazz fan, he visited New Orleans in 1958, and wound up accompanying

jazz historians William Russell and Richard Allen as they visited

local musicians to collect field recordings and oral histories for

their recently- established archive at Tulane University.

Born in 1934, Friedlander is Mr. Outside. He

studied in Los Angeles, but moved to New York where he worked as a

freelance photographer for outlets as varied as Esquire and Sports

Illustrated, as well as doing liner photos for Atlantic Records. As a

jazz fan, he visited New Orleans in 1958, and wound up accompanying

jazz historians William Russell and Richard Allen as they visited

local musicians to collect field recordings and oral histories for

their recently- established archive at Tulane University.

For almost three

decades, Friedlander visited New Orleans regularly and photographed

the city's culture of jazz. In a sense, he was following in the

footsteps of E.J. Bellocq, plates of whose photographs of Storyville,

the red-light district, from about 1912 were discovered only after

Bellocq's deah. Friedlander obtained the plates, developed them the

same sort of paper Bellocq used, and eventually issued them in three

books which established Bellocq's unique record of his city.

Friedlander's own

photographs are remarkable for their composition, which sets his

subjects into, and sometimes against, a wider landscape. Certainly

he's brilliant at catching the motion behind emotion: whether it's

the young girls in the 'second line' (Second Liners, 1968) or

Dixieland veterans playing in Preservation Hall (1982). But where

Hinton's musicians pose ironically in front of 'whites-only' or

'colored motel' signs, Friedlander makes his own irony;  one of his

most famous photos is a shot of the Young Tuxedo Brass Band (1959)

marching, through the rain, in front of a Pepsi-Cola billboard, from

which a well-coiffed white model brandishes a Pepsi bottle alongside

the slogan 'Look Smart'.

one of his

most famous photos is a shot of the Young Tuxedo Brass Band (1959)

marching, through the rain, in front of a Pepsi-Cola billboard, from

which a well-coiffed white model brandishes a Pepsi bottle alongside

the slogan 'Look Smart'.

The incongruity of this

African-American music, celebrating the joy and pain of life within a

culture often in direct, and always in cultural opposition to it, is

Friedlander's unlying theme. The masonic apron worn by one of the

members in a shot of Dejan's Olympia Brass Band (1982), the portrait

of Jesus hanging on the wall behind the bluesman Robert Pete Williams

(1973). Jesus and a bird cage are the only ornaments as he shoots

Williams in situ, and those portraits may be even more powerful than

the photographs of the jazz swagger of the bands. Kid Thomas

Valentine's stylised wire trumpets climb the wall behind him,

alongside a portrait of Martin Luther King. Albert Burbank's meagre

surroundings are enlivened by a small artificial Christmas tree,

standing on the box it came in. Louis Keppard sits in his chair

playing his guitar, framed by the window curtains behind him, with

the feel of a Goya portrait of a saint.

with

the feel of a Goya portrait of a saint.

It's a fascinating mix

of spontaneity and planning, much like jazz music itself, and it

takes its freshness and its power from Friedlander's not being a New

Orleans native, not being a musician, not taking this for granted,

not seeing things from the inside, as if they were the way they've

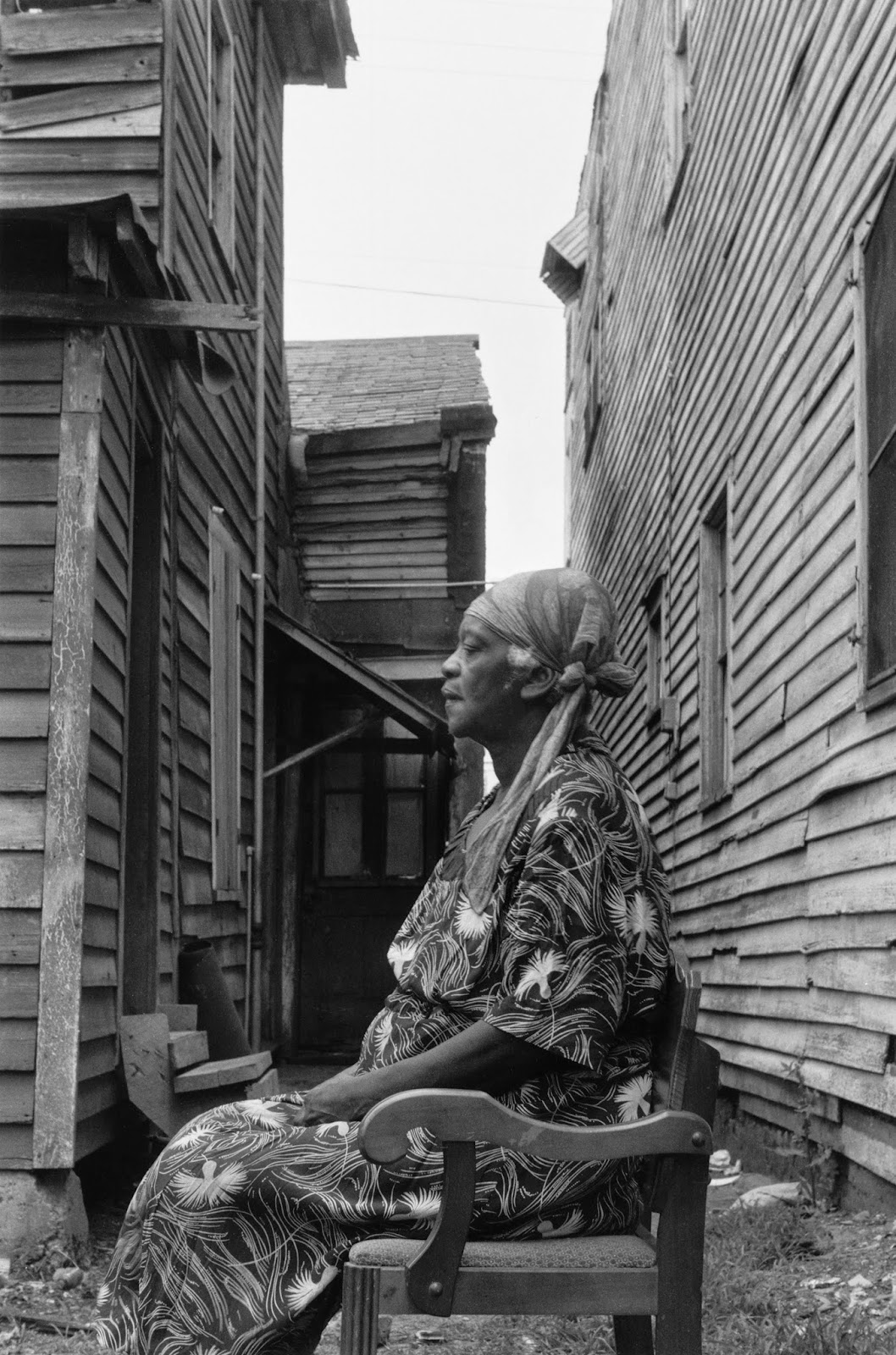

always been. And oddly, the image whose impression I took away most

tellingly was his portrait of Ann 'Mama Cookie' Cook (1958). She sits

in a short-backed wooden chair, in a good dress and a head-scarf, in

a small alleyway between two ranshackle houses. Her eyes are closed,

her back is straight. It speaks of dignity, strength, and of the

wearing-down struggle with life in the American South in the Fifties,

the struggle which music did so much to help them overcome.

JAZZ LIVES: PHOTOGRAPHS

BY MILT HINTON AND LEE FRIEDLANDER

Yale University Art

Gallery New Haven Connecticut through 7 September 2014

photo credits: all Lee Friedlander photographs c. and courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery

all Milt Hinton photographs c. and courtesy of Milton J Hinton Photographic Collection (www.milthinton.com)

Thursday 12 June 2014

SEA JOURNEY: A TWISTED SONNET

I came across the manuscript of this poem the other day; I don't recall when I wrote it, but it was published in Tokyo almost exactly twenty years ago, in a nice magazine called Printed Matter. It probably originated in the early 1980s, and was written out around 1990--I was trying to put together a sequence called Jazz Suite in those days, and this one was written around a Chick Corea tune as performed by the Gary Burton quintet on his Passengers album, which was released in 1977. This was the quartet with Pat Metheny, Steve Swallow, Dan Gottlieb, and the wonderful Eberhard Weber added as a second bass player. It's a beautiful tune, and Weber's pulsing bass lines really make it work. You can hear it here.

I've redone it considerably from the published version; we change in twenty years and time does things to our perceptions and how we express them; I think it's closer to the flow of the music now, and the bent-up sonnet is clearer now....

SEA JOURNEY

(Chick Corea/Gary Burton)

This is something

different from what we knew

Was true, when we

stared across the narrows

Between our pillows &

found ourselves lost

In wonder when storm

tossed thoughts inside find

Faces we had just

caressed, & whether we'd dare

To share our guesses.

Trying to trace form

Mirrored in moving

water, each impulse there

In the shifting spaces

of our lonely minds,

Where waves crashed &

broke, short of the places

We thought we'd choose.

Where we might share storms

Or lose. Might hold

each other & not get soaked

By tears. Then your

voice rose, like foam from wave,

Saying why do we roam

with the water near

If staying dry is what

we really crave?

Wednesday 4 June 2014

MEGAN ABBOTT'S GOT THE FEVER

Deenie Nash is a

teen-aged girl in a cold, gray town in the northern USA. Her brother

is a star hockey player, her father teaches at their high school, her

divorced mom lives a few towns away. Her circle of friends is fraught

with imbalance, the imperfect mixings along the chain, the way the

emotions of love and sex intensify at different paces. So far so

normal for small-town America. And then Deenie's friend Lise

collapses in fits, struck, as if possessed by a mystery illness

which, as it spreads, threatens to bring the whole town down into

chaos.

Deenie Nash is a

teen-aged girl in a cold, gray town in the northern USA. Her brother

is a star hockey player, her father teaches at their high school, her

divorced mom lives a few towns away. Her circle of friends is fraught

with imbalance, the imperfect mixings along the chain, the way the

emotions of love and sex intensify at different paces. So far so

normal for small-town America. And then Deenie's friend Lise

collapses in fits, struck, as if possessed by a mystery illness

which, as it spreads, threatens to bring the whole town down into

chaos.

The brilliance of Megan

Abbott's seventh novel is the way it constantly shifts the ground

from beneath you, the way it moves between tropes and genres almost

effortlessly. What is The Fever? Is it a teen-aged thriller

about the fragile psyches of girls on the brink of womanhood, in a

society where sex is out front all the time, but still treated as a

dirty secret behind the curtain? Certainly the adults of the earlier

generation do nothing to ease their children through this

ever-earlier ritual of so-called maturity? Is it a novel about the

abuse of modern science? Were vaccinations to help prevent sexual

infections responsible for these fits? Is it about mass-hysteria, a

Crucible-like dissection of

the weakness of adult society in the face of the power and threat

inherent in young sexuality? Or is there a supernatural force

at work, enacting a horror-movie's babysitter retribution against

these girls when they hit sexual activity?  At times Abbott seems to

be writing a sharply literate take on the 'weird menace' stories from

pulp magazines like Strange Tales, playing a very-knowing three-card

monte trick with the enthralled reader.

At times Abbott seems to

be writing a sharply literate take on the 'weird menace' stories from

pulp magazines like Strange Tales, playing a very-knowing three-card

monte trick with the enthralled reader.

At times Abbott seems to

be writing a sharply literate take on the 'weird menace' stories from

pulp magazines like Strange Tales, playing a very-knowing three-card

monte trick with the enthralled reader.

At times Abbott seems to

be writing a sharply literate take on the 'weird menace' stories from

pulp magazines like Strange Tales, playing a very-knowing three-card

monte trick with the enthralled reader.

This knowing approach

should not surprise anyone who's followed Megan Abbott's career. Her

first four novels, Die A Little, The Song Is You (see my review here),

Queenpin, and Bury Me Deep were noir fictons, but with

a difference; not so much told from a woman's perspective but with

the classic sexual tropes of noir reversed. Abbott's first book, The

Street Was Mine, was study of masculinity in hardboiled fiction

and film noir; her early novels were filling in the other side of the

story. It was something new to crime writing, something she made her

own.

With her fifth novel,

The End Of Everything, she switched gears. It's easy to see

where the now-common comparisons with Gillian Flynn arose, especially

once the book was named a Richard and Judy selection in Britain. But

the story of a disappeared 13-year girl, told from the point of view

of her best friend, reads like Flynn crossed with Vin Packer, a deft

mix of coming-of-age girlhood, the spectres of paedophilia and

incest, and the desperate intensity and doom of Fifties pulp. I wrote

then (you can read my review here) comparing the novel to Lolita,

about her fascinating obsessions, and I stand by that now. What I've

written above may seem overly analytical, but the remarkable thing

about Abbott's writing is how much it suggests and stands up to such

analysis, and how engrossing it is on its pure story-telling basis.

There is a dream-like sense in her prose, a fever-dream we follow

through to the end. I marvel at the result. Megan Abbott may be the

most original crime writer of the past decade, and she should be

treasured by readers of all sorts of fiction.

The End Of Everything, she switched gears. It's easy to see

where the now-common comparisons with Gillian Flynn arose, especially

once the book was named a Richard and Judy selection in Britain. But

the story of a disappeared 13-year girl, told from the point of view

of her best friend, reads like Flynn crossed with Vin Packer, a deft

mix of coming-of-age girlhood, the spectres of paedophilia and

incest, and the desperate intensity and doom of Fifties pulp. I wrote

then (you can read my review here) comparing the novel to Lolita,

about her fascinating obsessions, and I stand by that now. What I've

written above may seem overly analytical, but the remarkable thing

about Abbott's writing is how much it suggests and stands up to such

analysis, and how engrossing it is on its pure story-telling basis.

There is a dream-like sense in her prose, a fever-dream we follow

through to the end. I marvel at the result. Megan Abbott may be the

most original crime writer of the past decade, and she should be

treasured by readers of all sorts of fiction.

The End Of Everything, she switched gears. It's easy to see

where the now-common comparisons with Gillian Flynn arose, especially

once the book was named a Richard and Judy selection in Britain. But

the story of a disappeared 13-year girl, told from the point of view

of her best friend, reads like Flynn crossed with Vin Packer, a deft

mix of coming-of-age girlhood, the spectres of paedophilia and

incest, and the desperate intensity and doom of Fifties pulp. I wrote

then (you can read my review here) comparing the novel to Lolita,

about her fascinating obsessions, and I stand by that now. What I've

written above may seem overly analytical, but the remarkable thing

about Abbott's writing is how much it suggests and stands up to such

analysis, and how engrossing it is on its pure story-telling basis.

There is a dream-like sense in her prose, a fever-dream we follow

through to the end. I marvel at the result. Megan Abbott may be the

most original crime writer of the past decade, and she should be

treasured by readers of all sorts of fiction.

The End Of Everything, she switched gears. It's easy to see

where the now-common comparisons with Gillian Flynn arose, especially

once the book was named a Richard and Judy selection in Britain. But

the story of a disappeared 13-year girl, told from the point of view

of her best friend, reads like Flynn crossed with Vin Packer, a deft

mix of coming-of-age girlhood, the spectres of paedophilia and

incest, and the desperate intensity and doom of Fifties pulp. I wrote

then (you can read my review here) comparing the novel to Lolita,

about her fascinating obsessions, and I stand by that now. What I've

written above may seem overly analytical, but the remarkable thing

about Abbott's writing is how much it suggests and stands up to such

analysis, and how engrossing it is on its pure story-telling basis.

There is a dream-like sense in her prose, a fever-dream we follow

through to the end. I marvel at the result. Megan Abbott may be the

most original crime writer of the past decade, and she should be

treasured by readers of all sorts of fiction.

The Fever by Megan

Abbott

Picador, £14.99, ISBN

9781447226321

note; this review will also appear at Crime Time (www.crimtime.co.uk)

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)