My obituary of Norman Schwarzkopf, the general who led Operation Desert Storm, is online at the Guardian (link to it here) and may be in the paper paper today (Saturday 28th). There are a few changes to what I wrote, as I was unavailable for the editing process after writing it on short notice, but they are mostly changes of omission. I will confess that after studying his life, I was more favorably inclined to Schwarzkopf than I had thought I would be--it is not his fault that America tends to provide its military heroes with unquestioning adulation, nor that the American military tends to reward them with a prolifigacy which might embarrass the soldiers of the past. He also didn't seem to be a careerist who rose quickly through the bureaucratic army, like say, Colin Powell, whose rise began when he helped cover up and spin the My Lai massacre. Although I don't agree with the pervasive belief in the 'Vietnam Syndrome', I could respect the way Schwarzkopf decided to fight his war to win it, with the fewest possible casualties on his side, and with the public presented with a positive media experience of it. It helped that the First Iraq War was relatively more straightforward than the second; Iraq had indeed provided a causus belli.

My obituary of Norman Schwarzkopf, the general who led Operation Desert Storm, is online at the Guardian (link to it here) and may be in the paper paper today (Saturday 28th). There are a few changes to what I wrote, as I was unavailable for the editing process after writing it on short notice, but they are mostly changes of omission. I will confess that after studying his life, I was more favorably inclined to Schwarzkopf than I had thought I would be--it is not his fault that America tends to provide its military heroes with unquestioning adulation, nor that the American military tends to reward them with a prolifigacy which might embarrass the soldiers of the past. He also didn't seem to be a careerist who rose quickly through the bureaucratic army, like say, Colin Powell, whose rise began when he helped cover up and spin the My Lai massacre. Although I don't agree with the pervasive belief in the 'Vietnam Syndrome', I could respect the way Schwarzkopf decided to fight his war to win it, with the fewest possible casualties on his side, and with the public presented with a positive media experience of it. It helped that the First Iraq War was relatively more straightforward than the second; Iraq had indeed provided a causus belli.Schwarzkopf's biggest error, in retrospect, was allowing the Iraqis the means to put down the insurrections that rose up against Saddam--but his instinct against becoming an occupying power in Iraq was sound, and the ultimate political decisions, of course, were not his. As we saw in the Second Iraq War, and in Afghanistan, he was absolutely right on that count. Although he supported the 2003 invasion, that support was quickly moderated by his realisation the war was being fought on fabricated grounds, that 'mission creep' led to an occupation far worse than he had imagined a decade earlier, and by his intense dislike of Donald Rumsfeld's ways of waging war, using reservists and contractors to replace the standing army.

His public stances on that war were not profound, but his absence of cheerleading for the second Bush administration spoke volumes. I also found the quiet life he led in Tampa relatively admirable, as he was active with charity work alongside the usual board memberships on arms companies. That he never sought political office or power, or to cash in publicly on his name seems to me the sign of a man with a strong personal compass. A contrast, say, to David Petraeus.

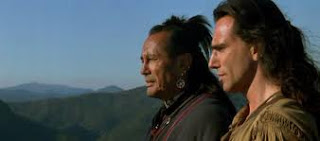

The paper cut a few interesting things about his father, whose main fame comes because he led the New Jersey State Police

during their investigation of the Lindbergh Kidnapping, the 1930s' crime of the century. (That's him with Lindbergh in the photo on the right). The guilt of Bruno Richard Hauptman remains in some doubt, and his role in getting Hauptman convicted was crucial. For some reason the paper took out what became the most lasting legacy of his consultancies, for the Shah of Iran just after a CIA-backed coup installed him in power. Schwarzkopf, Sr. basically organised the SAVAK, the Iranian secret police, and it must be said, he did a good job because they were efficient in their work. It was because of that work that Norman was educated in Tehran and in Europe, which I think had a profound effect on his world-view.

during their investigation of the Lindbergh Kidnapping, the 1930s' crime of the century. (That's him with Lindbergh in the photo on the right). The guilt of Bruno Richard Hauptman remains in some doubt, and his role in getting Hauptman convicted was crucial. For some reason the paper took out what became the most lasting legacy of his consultancies, for the Shah of Iran just after a CIA-backed coup installed him in power. Schwarzkopf, Sr. basically organised the SAVAK, the Iranian secret police, and it must be said, he did a good job because they were efficient in their work. It was because of that work that Norman was educated in Tehran and in Europe, which I think had a profound effect on his world-view.The legacy of the Shah and his Savak, of course, was the Ayatollah Homeni, the Embassy Hostages, the October Surprise and Reagan's election, and then the Iran/Iraq wars, where we were, whisper it softly now, on Iraq's side, and provided them with the weapons of mass destruction they used first on Iranian troops and then on their own people, pace the famous photo of Rumsfeld and his buddy-in-democracy Saddam shaking hands after another arms deal had been done. Eventually, that would lead to Desert Storm, where, as we discovered a decade later, we could have done a lot worse than a general like Norman Schwarzkopf.