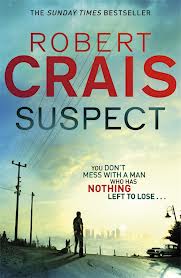

There is a theme

running through Robert Crais' work, whether it's the Elvis Cole and

Joe Pike novels or not, and that is relationships. Familial,

romantic, partnerships are the currency of Crais' characters, and for

him character is indeed, as F. Scott Fitzgerald famously observed,

action. Though his books often seem fast-paced, when you look at them

closely you'll see him weave myriad plot strands together and, as

befits someone who was a highly successful writer of episodic

television, usually resolve them quickly. What isn't resolved quickly

is whatever series of questions Crais has made his characters face

about their relationships; sometimes that resolution mimics the

high-speed finales, sometimes it runs parallel, and sometimes it is

resolved in quite an opposite way altogether.

There is a theme

running through Robert Crais' work, whether it's the Elvis Cole and

Joe Pike novels or not, and that is relationships. Familial,

romantic, partnerships are the currency of Crais' characters, and for

him character is indeed, as F. Scott Fitzgerald famously observed,

action. Though his books often seem fast-paced, when you look at them

closely you'll see him weave myriad plot strands together and, as

befits someone who was a highly successful writer of episodic

television, usually resolve them quickly. What isn't resolved quickly

is whatever series of questions Crais has made his characters face

about their relationships; sometimes that resolution mimics the

high-speed finales, sometimes it runs parallel, and sometimes it is

resolved in quite an opposite way altogether.

In Suspect, the

relationship in question is between Scott James, an LA cop who lost

his partner, was severely wounded himself, in a massive shootout, and

his new partner, a German shepherd named Maggie who herself lost a

partner and was severely wounded in Afghanistan.

It takes a brave writer

to try not to have animals upstage his story, and Crais makes it work

almost immediately; the prologue in Afghanistan is superbly judged.

He makes Maggie a real character with some of the most touching

writing I've read in the crime field in ages. Using animal point of

view is equally risky, but again, Crais pulls it off, and it's

necessary in the sense that we are dealing with two damaged beings,

whose path to each other reflects that damage even as they heal. So

Scott has to prove himself as a dog handler, in order to remain what

he wants to be, a working cop, but he also has to try to solve the

mystery of the shooting that killed his former partner, Stephanie, to

stop his feeling he left her behind.

It works well. As Scott

gets closer to the truth, he finds himself ensnared. Perhaps it would

have been good to see the ultimate villain fleshed out a little more

fully, or foreshadowed slightly more strongly, and perhaps Scott

could have been left hanging out in the wind for a longer, more

suspenseful, time. In an afterword, Crais acknowledges a certain

amount of compression of time in the dog training, but it's easy to

see why he wanted to maintain the pace as he does, to in effect force

the new partnership to a point of crisis, to see if the bonding

sticks, and to see if both partners can begin to trust the world

again. It is a bravura piece of writing, and it seems a natural for a

movie—after all, it's been too long since we've seen heroic dogs on

our screens.

Orion, £12.99, ISBN 9781409127703

NOTE: This review will also appear at Crime Time (www.crimetime.co.uk)